Complete Napa Valley California Wine History from Early 1800’s to Today

Everything about the complete history of Napa Valley, the California wine-making industry, and Sonoma County history from the 1800s to today. It covers everything you want to know and more about the wines, wineries, winemakers, and vineyards in the Napa Valley and California.

If you want to read detailed profiles on specific, current wines and producers of California Wine with images, tasting notes, and technical information, California Wine Producer Profiles If you want to read about the most important grapes used to produce California wine, please see our Guide to California Wine Grapes

First Vineyards in California: The first vines were planted in California as far back as the late 1700′s. While history shows vines were planted in 1683, it is not likely those first vineyards were developed, as the areas they were planted in were abandoned. In 1779, a group of missionaries led by Father Junipero Serra planted vineyards for use in all 9 of the Missions he founded.

Those early vines were cultivated to produce wine used for religious purposes. The initial plantings were not specific grape varieties. They were field blends, which due to their use by the Church became known as Mission grapes.

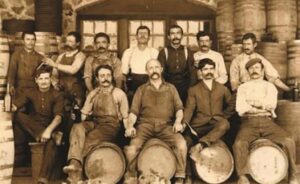

The name came from the fact that they were planted by early Missionaries. The commercial birth of the wine industry took hold not much later in the mid to late 1800′s. Thanks to a small group of European emigrants, Napa and Sonoma got their start when Abraham Lincoln was President! In fact, President Lincoln was the first President to purchase and serve California wine.

Before Napa Valley was known for producing quality wine, many of the most popular American wines came from New York, Virginia, Ohio, and Missouri. In fact, vineyards were sprouting all over the place in Southern California before Napa and much of Northern California were cultivated.

It is known that European grape varieties were being planted in Los Angeles and Anaheim in the 1830s. The perfectly named Jean Louis Vignes opened the first commercial winery in California in 1833. Jean Louis Vignes was quickly followed in Southern California by William Wolfskill who owned more than 145 acres of vineyards in Los Angeles and Southern California by the late 1830s. Charles Kohler and John Frohling started planting in what would soon become Anaheim, California, close to Los Angeles in 1852, creating the Los Angeles Vineyard Society.

In 1859, the Los Angeles wine industry was given an added boost when the city agreed that no taxes shall be imposed on land used for planting grapes. East of Los Angeles, in Rancho Cucamonga, which is not far from San Bernardino, vines were planted in 1838. Santa Ana and other areas south of Los Angeles also saw the planting of vines.

The birth of Napa Valley: It could be said that the history of Napa Valley begins when Joseph Osborne started planting vines on a 1,800-acre tract of land he named Oak Knoll in the 1850s.

That original vineyard has been split and re-split several times over the decades, but it has given birth to several of the best benchland vineyards in the valley. However, much of the credit for planting the first vines in Napa goes to George Calvert Yount.

The land George C. Yount first began cultivating was given to him as a grant from the Mexican government, as California was not yet awarded statehood, and was still part of Mexico. George Calvert Yount began planting vineyards as far back as 1836 in Northern California.

The famous town of Yountville carries his name. Thanks to Samuel Brannan, the creation of Calistoga was not far behind. In 1859, Samuel Brannan purchased a large tract of land where he began planting vines, called Agua Caliente Ranch. With over 100 acres of vines, he named the region, Calistoga. Other vineyards also came into fruition in 1859 when Frederick Sigrist and John Sigrist began planting vines in land that is now owned by Hendry Ranch.

While George C. Yount was the first person to seriously plant vines, Napa Valley history was made by John Patchett, who gets credit for creating the first official vineyard and winery in the Napa Valley. John Patchett began planting vines in 1854 and started producing wine just three years later in 1857. John Patchett constructed his cellar in 1859. The following year his wine received an official review.

This is probably the first official review of any California wine. Composed by the Robert Parker of his day and published in “California Farmer Magazine,” the review said, “The white wine was light, clear and brilliant and very superior indeed; his red wine was excellent; we saw superior brandy, too.” His winemaker was Charles Krug, who would go on to form his own winery in a few years.

Wine was growing enough in popularity that a second wine journal was born, The Pacific Wine and Spirit Review. Still, the California wine industry was so young, when Patchett made his first vintage, they did not even have a grape press. They used an old cider press, as that was all they had.

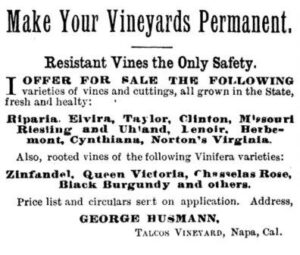

In the formative years of the California wine industry, vineyards were initially planted with as you know, Mission grapes. However, Zinfandel and Petite Sirah were also widely planted along with a myriad of other French, Italian, and German grape varietals including Grenache, Riesling, Malbec, Sauvignon Blanc, Sauvignon Vert, Hamburg, Semillon, Flame Tokay, Petit Verdot, Furmint, Pinot Noir, Gamay, Muscadelle, Cabernet Franc, Muscat, Carmenere and Cabernet Sauvignon to name a few.

The true pioneers of California Wine: With more acreage than Napa, Sonoma County aided by its myriad of soil types, terroirs, cooler climate, and easy access to the region as well as for shipping began developing before the Napa Valley.

The history of Sonoma County is important and easy to recall because some of those first wineries are what started the California wine industry. And amazingly, a few of those early wineries are still in existence today.

For example; Buena Vista in Sonoma was founded in 1857, Gundlach Bundschu, also in Sonoma was created in 1858. As those two estates were truly important commercial California wineries, it can be said that Sonoma is actually the official birthplace of the California wine industry in Northern California. Charles Kohler and John Frohling formed Kohler & Frohling Wines in 1854, (In what is now Jack London Historical Park) using purchased grapes, before planting their own vineyards in 1857. The Korbel brothers began making the first Champagne-style wines in Sonoma during the 1880s.

Napa Valley history shows that the region really gets its start when the Charles Krug winery in Napa was founded in 1861. Other wineries quickly followed. Jacob Schram founded Schramsberg in 1862. Schramsberg became so popular that President Benjamin Harrison, the 23rd President of the United States served it in the White House at official functions.

John Lewelling began planting vines in the Napa Valley in 1864. Mt. Veeder, which took its name from Peter Veeder also began to see vines planted in 1864 by Captain Stalham Wing, who inspired the eventual naming of Wing Canyon.

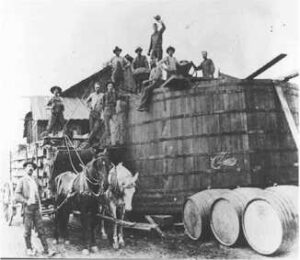

John Steckler cultivated part of a massive 367-acre estate with vines, which is now used by Staglin. Hamilton Walker Crabb came next in 1868. Hamilton W Crabb purchased 240 acres of what was still farmland from the family of George Yount. This land eventually became the famous To-Kalon vineyard.

I am not sure if Hamilton Crabb knew this was great vineyard land, due to its mixture of slopes and elevations with its loam and gravel soils and rocks with clay soil on the valley floor. Or was it just blind luck? Regardless, what became To-Kalon, turned out to be one of the best vineyard sites in all of Napa.

In 1872 Hamilton Crabb founded Hermosa Vineyards. Hamilton Crabb was extremely successful and by 1878, he was one of the largest vineyard landowners in Napa Valley. The early success of Charles Krug and Hamilton Crabb spurred other growers to cultivate vines in Napa.

The Cedar Knoll Vineyard was planted in the 1870s. By 1880, more than 3,500 acres were planted with vines with more than 40 wineries actively producing and selling wine. In just a decade, from 1880 to 1890, the number of plantings in the valley exploded from 3,500 acres to more than 18,000 acres and with the number of wineries expanding to almost 200!

The town, which became Napa City is by necessity, important to the region, as that is where the majority of business took place. The actual city was initially developed by Nathan Coombs in 1847. This was 2 years before California was even granted statehood. Nathan Coombs was the inspiration behind the naming of Coombsville.

Corresponding with the burgeoning wine industry, the first, large commercial winery opened in Napa in 1872, Uncle Sam Wine Cellars. Uncle Sam Wine Cellars had the capacity to produce and bottle up to 2,000,000 bottles of wine! By the 1880s, their business had almost doubled in size. Their location, on the Napa Riverbank, made shipping easy. They were soon followed by the Napa Valley Wine Company.

In 1881 Hamilton Crabb purchased 119 acres from Eliza Yount for $100 per acre, which marked the birth of the To-Kalon vineyard. While it sounds amazingly cheap today, $100 was a lot of money at the time. Hamilton Crabb knew great soil when he saw it. Another smaller portion of the original vineyards planted by Hamilton Crabb are currently used by the Detert family and the MacDonald Family.

Those initial 30 acres of vines were sold by Caroline Stelling to Hedwig Detert in 1954. The price at the time was $650 per acre. That parcel was then renamed Detert Vineyard. In the later part of the 1950s, the vineyard was split between Gunther Detert, and Allen Horton, who is a relative of the Detert family.

The parcel belonging to Allen Horton is where the MacDonald family inherited their part of the To-Kalon Vineyard. For 30 years, the harvest was sold to Robert Mondavi. That changed in 2010 when the family began producing their own wine.

You can also count the vineyards in use today by Opus One and Robert Mondavi, as part of the vineyards cultivated by Hamilton Crabb. In 1886, Crabb changed the name of his winery from Hermosa to the To-Kalon wine company, which by that time, became one of the best-known names making wine in the Napa Valley. The To-Kalon Wine Company produced red wine, sweet wines labeled as Sauternes, Port, white wine, and Brandy, as you can see from the advertisement.

At his peak, Hamilton Crabb the To-Kalon Vineyard grew to 650 acres of vines. Crabb was by then capable of producing close to 150,000 cases of wine. The vineyards were planted to several different grape varieties including black burgundy and Tannat, a grape that was in use in Bordeaux at the time.

Due to the ravages of phylloxera, Hamilton Crabb died broke in 1899. At close to the same time, Thomas Rutherford, who got his start with a wedding gift of about 1,000 acres of vines in 1864 when he married the granddaughter of George C Yount.

Thomas Rutherford was cultivating vineyard land in what would become the Rutherford appellation. In 1874, the Sunny St. Helena Winery, which has since changed names to Merryvale, was first cultivated by Joseph Ghisletta. About 60 years later, the Sunny St. Helena Winery was about to become very important in the history of Napa Valley.

The Beringer winery was created in 1875 by Jacob Beringer and Fredrick Beringer, who previously worked for Charles Krug. Simi came into being in 1876. What became Inglenook was born in 1879. Founded by William C. Watson in 1873, Gustave Niebaum purchased the estate and turned it into one of the most famous wines of the day. That same year, Charles Lemme began purchasing land and planting vines for La Perla. The vineyard was sold to the Schilling family, owners of the famous spice company before it was acquired by Spring Mountain Vineyard.

Producing what was thought of as a true Bordeaux-styled wine, Inglenook became even more popular after the wine won a gold medal at the world’s fair, which was held in Paris in 1889.

Inglenook wines were considered as some of the best California could offer, and they were soon provided to passengers on the Canadian Pacific Railroad in their First Class dining cars. By the time Gustave Niebaum died in 1908, he owned 300 acres of vines.

The Inglenook winery was modeled after the best Left Bank Bordeaux chateau. The estate remained in the same family’s hands eventually passing to John Daniels through marriage in 1936.

The Migliavacca wine company, another Napa winery also earned a gold medal in Paris that year. Beringer and Niebaum were not the only new wineries in the 1870s, John Benson cultivated the 84 acre Far Niente vineyard with plantings of Zinfandel, Chasselas, and Sauvignon Vert.

In 1876, Morris Estee founded Hedgeside Vineyards, just off the Silverado Trail. What makes this important is that Estee and Hedgeside were perhaps the first wineries to plant Cabernet Sauvignon in Napa, producing a wine sold as a Claret. The vineyards used for Hedgeside are now owned by Quail Ridge.

Charles Hopper first planted what we now know as the Missouri Hopper Vineyard in 1873. The parcel for this vineyard was purchased from George Yount. A part of the original Missouri Hopper vineyard is now used to produce Ulysses, the wine from Christian Moueix, as well as several other top wines from the region today.

While most of the plantings were done on the valley floor in those days, perhaps the first 2 emigres from Bordeaux to make their way to the Napa Valley, Jean Brun and WJ Chaix, began planting on Howell Mountain in 1877. They formed the Nouveau Medoc winery, which is now better known as Chateau Woltner. The Woltner family went on to own the famous Chateau La Mission Haut Brion vineyards in Bordeaux for several decades.

Burgess Winery, also on Howell Mountain, was founded in 1870 when Charles M. Burgess bought 137 acres of land. The first plantings and winery in Conn Valley took place in 1875, under the name of Germain Crochet. In 1880, William Angwin, the local Pastor planted a small vineyard on Howell Mountain. He must have been popular because there is a town named after Angwin. Winfield S. Keyes was another Howell Mountain pioneer, who began planting vines in 1888.

The 1880s were a good period for growth in the Napa Valley. While the Vine Cliff Vineyard was first cultivated in 1866, the winery came into its own by 1880. Owned by George S. Burrage at the time, their Vine Cliff Vineyard wine was probably the most expensive wine made in the Napa Valley selling for a whopping $15 per case! That is a lot of money in those days.

Charles Pritchard planted Zinfandel and built a tiny cabin on what became known as Pritchard Hill in 1880. Zinfandel quickly grew in popularity. In fact, there was a steamship that traveled regularly between San Francisco and Napa called the Zinfandel Steamer!

The Crane vineyard, named after Dr. George Crane was planted starting in 1880. At its peak, Dr. George Crane owned 300 acres of vines. Many of those acres were purchased for as little as $6 per acre!

Dr. Crane hired the associate of Charles Krug, Henry Pellet to make his wine. 1880 proved to be a year of expansion for the fledgling California wine industry, George Schoenwald planted the vineyard that is in use today by the Montebello Winery. In 1881, the Franco-Swiss Farming Company cultivated a large portion of their 143-acre parcel wine vines that is now used by Seavey Vineyards.

Alexander Valley, Dry Creek Valley and the Santa Cruz Mountains were also first being cultivated in the late 1880s. In Calistoga, Chateau Montelena was created by Alfred Tubbs in 1882 when he planted 220 acres of land. His first plantings were not distinguished.

But on a trip to France, he came back with vine cuttings from Chateau d’Yquem and Lafite Rothschild! Alfred Tubbs was one of the first growers to begin planting phylloxera-resistant rootstock.

Just a bit south, what later became Spottswoode was founded by George Schonewald in 1882 as well. Edward Stanly began cultivating 170 acres of land in Carneros in the mid-1880s. 1885 saw the birth of Ridge Vineyards, which was first cultivated by Osea Perrone, after he bought 180 acres of land in the Santa Cruz Mountains on the Monte Bello Ridge.

In the mid-1880s, the Eshcol Ranch was cultivated and developed by James Goodman and George Goodman. Today, it is the site for Trefethen vineyards. In 1889, Mayacamas, the first of the famous mountain vineyards in the Napa Valley came into being thanks to John Henry Fischer.

Zinfandel played an important part in Napa Valley’s history. Zinfandel was being planted in the latter part of the 19th century. The Hendry vineyard began being planted in the 1860s. The Library vineyard started to be cultivated in the 1880s. The Pagani vineyard was cultivated in 1884. Fortune Chevalier created Chateau Chevalier with 25 acres of vines, mostly planted to Zinfandel. The vineyard is now part of Spring Mountain Vineyard. Spottswoode began planting Zinfandel in the 1890s and Hayne Vineyard was planted in 1902.

The Moore vineyard in Coombsville was not far behind as it was planted in 1905. Vineyards were cropping up in other parts of Northern California in those formative years. George West and William West founded the El Pinal Winery in 1858 in Stockton and Joseph Spenker began planting Zinfandel, Cinsault, and other grapes in Lodi during 1889, in what is known today as the Bechthold Vineyard.

By this time, the news had spread about the perfect combination of a warm climate, great soil, and cheap land. During the formative years in Napa Valley, as you may have noted, most of the original pioneers of the Napa Valley were men. But that was not always the case.

In 1881, Josephine Tychson became the first female grower, vintner, and winery owner in the Napa Valley when she and her husband John Tychson planted vineyards on a 147-acre parcel of land in St. Helena. By the 1890s, Josephine Tychson had 65 planted acres. That vineyard eventually gave birth to Freemark Abbey and Colgin Cellars, with their aptly named, Tychson Hill wine.

The history of Napa Valley shows that those early years were difficult and expensive for the pioneers of the California wine industry. Glass bottles were pricey and hard to find. It was not uncommon for producers to reuse empty bottles, especially those that originally contained imported wine. Because bottles were hand-blown and expensive to deliver, they could cost as much as .10 to .12 cents per bottle.

This was at a time when California wine was sold by the gallon. The cost for wine varied from as little as .25 per gallon to $2.00 for the best wines. On average, a bottle of wine cost between 20 cents to 35 cents in the early 1860s. Yields were high. On average, growers could count on close to 5 tons per acre, or roughly 400 cases per acre.

In 1856, only 225 acres of Napa were cultivated with vines. From that point forward, the growth was incredible! 1866 saw 3,740 acres planted and in 1875, 24,664 acres were planted. As you can see, slowly but surely, Napa Valley was beginning to thrive as a wine region.

Going back to the number of cultivated acres in 1875 for a moment, this is an interesting statistic, because it was not until 100 years later, in 1975, that Napa had that same amount of plantings. The decline took place due to phylloxera, prohibition, and the depression, all of which took decades for the region to make a full recovery.

Exporting California Wine in the Formative Years of Napa Valley

Charles Kohler and John Frohling who first started making wine in 1854 from purchased grapes in Sonoma began producing wine bottles at their Pacific Glassworks company in the 1860s. They needed the bottles for their own wines as well as to sell to other burgeoning California wineries and to supply the first distribution and export company for wine, Kohler and Frohling.

Some of the early efforts at exporting California wine faced subversive marketing issues when competitors accused California wineries of fraud, adulteration of their product, and falsification on their labels. This continued for close to 20 years until California wine started earning popularity with consumers from outside the state.

Following the end of the Civil War, California wine exports doubled from 100,000 cases to 225,000 cases by 1870. While California wines were exported to other countries, most notably, Europe, South America, Central America, Mexico, Canada, and China. Most of the wine exported from California in those days was delivered to the east coast of America, especially New York, Philadelphia, Boston, and Baltimore.

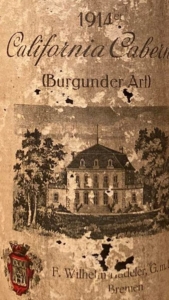

With time, wine from the Golden State became so popular, wineries from outside the state began labeling and selling their wine as California wine. This brought about the first, national pure wine law. Clearly, California wine was exported to Europe by Negociants who purchased the wine while still in barrel, bottled, and sold it in Europe. You can see this bottle from 1914, of Cabernet Sauvignon showing the wine was sold by a German Negociant.

Charles Krug established his winery due north of St. Helena in 1861. The now-famous Capella vineyard, also located in St. Helena was cultivated in 1869. This was followed by a winery founded by Henry Pellet in 1873, the year of the great depression.

Henry Pellet and Charles Krug created a joint venture to ship their wine together. Due to the somewhat successful Charles Krug Winery, other vineyards in the Napa Valley began popping up.

The wines did not sell well. Of course, part of that was due to lack of quality coupled with prices that were too high. At the time, shipping by train was quite pricey. It could cost as much as $4.80 per case to transport by railroad from California to the East Coast in the late 1860s. This made California wine far too expensive to ship to the east coast.

Because tariffs were low, imported wine from France and Italy was sold cheaply. Bordeaux was seen as a wine of quality. People knew Bordeaux was produced from Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, and Cabernet Franc. That was not the case with California wines that were mostly the product of field blends and low-quality Mission grapes.

A portion of California wines was also fortified at the time because consumers liked sweeter tasting wines and the fortification acted as a preservative.

A pivotal event in the development of the California wine industry came about thanks to the California Gold Rush and the completion of the transcontinental railway. Countless new settlers, merchants, farmers, and prospectors, as well as wealthy speculators, moved into the area.

To give you an idea of the massive growth spurt, San Francisco exploded from 1,000 residents to more than 25,000 residents in less than 12 months! People began moving from the big city, populating many of the best wine-growing regions in Napa County, Sonoma County, and other burgeoning viticultural areas.

Sonoma becomes established: The history of Sonoma really begins with Agoston Haraszthy. Agoston Haraszthy, a Hungarian immigrant, brought close to 100,000 grapevine cuttings from Europe, (mostly vines from Hungary) to the area. In fact, credit belongs to Agoston Haraszthy for introducing the first European vines and grape varieties to California in 1852. Prior to Haraszthy, almost all the vines planted in California were of the Mission variety.

His initial idea was to plant in San Mateo and San Francisco. But the cold, foggy mornings caused him to seek sunnier land for his grapevines. Agoston Haraszthy went on to found the Buena Vista Vinicultural Society, which eventually became the Buena Vista Winery in Sonoma.

In 1859, after an extensive study on soils and climates for the cultivation of vineyards, the agricultural journal, “California Farmer” published the first paper extolling the virtues of planting European grape varieties and the potential profits to be earned by growing grapes.

When Agoston Haraszthy moved his operations, he uprooted his vines from San Francisco and replanted them in Sonoma at the newly named Buena Vista Winery. At the time of his early plantings, the land was cheap in Sonoma, selling for as little as $6 per acre. In time, due to his success, prices climbed to $150 per acre. Agoston Haraszthy also deserves credit for his viticulture and wine-making advances.

Agoston Haraszthy was perhaps the first California wine producer to dig his own caves, plant on hillsides and because oak was hard to find, he began producing barrels from redwood to age his wine. Following the European custom, he did not irrigate, he dry-farmed his vineyards.

Agoston Haraszthy needed like-minded people who shared his passion for wine. He began spreading the word of his success hoping to bring other like-minded growers to northern California. In fact, Agoston Haraszthy hired both Charles Krug and John Patchett.

By 1860, Haraszthy owned more than 5,000 acres of land. 1861 saw Agoston Haraszthy return to Europe to collect 200,000 cuttings and vines consisting of 1,400 different grape varieties for planting in California for his vineyards and those of other growers in the region. In 1862, with a total production estimated to be close to 15,000 cases, he was already successfully bottling Zinfandel.

Other grape varieties planted in his vineyards included Riesling, Traminer, Flame Tokay, Black Morocco, and Sultana. During the 1860s the most popular California wines consisted of white wines, sweet wines, and later, sparkling wines. The level of production for the Buena Vista Vinicultural Society in the 1860s eventually rose to 50,000 cases of wine per year!

By 1870, they were producing their version of Champagne. The Buena Vista sparkling wine sold for the princely sum of $1.00 per bottle. While this was less than the cost of true champagne, it was still expensive when you consider that average salaries were not much more than $1 per day.

Agoston Haraszthy was not the only pioneer in Sonoma during those early days. Some of the vineyards in the region we know today were planted in the late 1800s including The Old Hill Ranch vineyard, which was cultivated in 1852 by William McPherson Hill.

The Madrone Ranch vineyard was planted by General William T. Sherman and General Joe Hooker in 1854. Both Generals played important roles in the Civil War. This was soon followed by Chelli, Jackass Hill, Maggie’s Reserve, Martinelli Road, Saitone, Wellington, and others.

The popularity of California wine exploded wine from its early years in the 1850s. To give you an idea, in 1850, the total production of California wine was close to 30,000 cases. By the end of the 1860s, production expanded to 125,000 cases. By the close of the 1870s, it’s estimated that more than 1,000,000 cases of wine were produced each year!

In late 1875, the three leading California wine-making pioneers, Charles Krug, Henry Pellet, and Seneca Ewer created the St. Helena Viticultural Club, which later became the St. Helena Viticultural society.

The St. Helena Viticultural Club consisted of other winemakers and vineyard owners who shared the same problems and dreams. Together they agreed that to improve the quality of California wines, they needed to remove the Mission grapes, focusing on cultivating French and Italian grape varieties as well as reduce the need for chaptalization.

The industry received an added boost thanks to the tariff act of 1864, which increased duties on imported wine, making California wine more attractive. To further aid and promote sales of California wine, plus make it a more profitable industry, excise taxes were reduced to zero for producers. Just as things were starting to move forward, California vineyards were attacked by Phylloxera.

The Phylloxera epidemic The Phylloxera epidemic was born in 1863. The spread of Phylloxera is said to have come from native American grapes which were brought to the famous English Botanical Gardens.

Those American grapevine cuttings carried a specific root louse that attacks and kills the roots of a vine. The first sights of Phylloxera in the USA seem to have taken place in Sonoma at Buena Vista vineyards.

The insects migrated to Napa starting in 1877 and were in full force just before the turn of the century. Phylloxera spread like wildfire in Europe decimating most of the European vineyards. Close to 90% of all European grapevines were destroyed.

Both the famous names and the ordinary estates across Bordeaux, Burgundy, Italy, and other regions were ruined. It took only 2 decades for the incredible amount of destruction to take place all over the world!

While several treatments were developed, the only practical solution was to graft the Vinifera vines onto the American rootstocks like Rupestris. St. Georges rootstock was soon preferred for most of the vineyards in Napa Valley, due to its ability to resist phylloxera.

A young French native, Georges de Latour was ready to sell this new rootstock to growers all over California. Because Phylloxera is indigenous to North America, local varieties had a natural resistance (but make poor quality wine), which explains why a cure and replanting were needed.

Most California vineyards needed to be replanted using only local rootstocks. One of the most popular varieties being planted after Phylloxera was Zinfandel. Those plantings explain why we have so many old Zinfandel vines in California.

While Phylloxera was one of the major issues facing growers of the day, none of the problems dulled the enthusiasm for making wine in the Golden State. Even the great depression of 1873 to 1876 did not curtail the growth of the California wine industry. However, it’s important to note that growers during those years were faced with hard times and plummeting prices. Many previously successful vintners went bankrupt.

It took years for the fledgling California wine industry to recover. It took a combination of increased quality, the removal of Mission grapes, and better economic conditions to rebuild the industry. By the late 1880s, the future of California wine began improving. In fact, by 1890, the northern California area had grown in popularity so much, that more than 100 people in just St. Helena were now producing wine!

The high protectionist tariffs levied against French wine in 1879, (thanks to the lobbying efforts of California wineries) coupled with the small production of European wines, due to the ravages of Phylloxera made California wine more popular than ever.

With the fledgling California wine industry starting to take hold, in 1880, thanks to the efforts of Dr. Eugene Hilgard, the first wine research center in the new world was born. Dr. Eugene Hilgard was able to request that the California State Legislature fund a program for wine research at the University of California.

The initial funding was for $3,000, which was a large sum of money in 1880! Dr. Eugene Hilgard, a noted soil scientist began studying which grapes were best suited for the climate, soil, and terroir of California with his newly funded “California Agricultural Experiment Station.”

More than a half-century later, that initial program turned into the current Agricultural Extension Program at The University of California Davis, which operates one of the world’s leading programs for the study of wine today.

1890 proved to be an important year for the young, struggling California wine industry. Records show almost 11 Million cases of California wine were produced! To help promote the sale and reputation of all those millions of cases of wine, numerous vintners entered their wine into competitions held in Paris for the World’s exhibition. Several California wineries won gold medals! That same year, in 1890, the Nichelini Family Winery came into being. Located in Chiles Valley, the winery remains in the hands of direct descendants of Anton Nichelini, making them the only historical winery still owned by the original founding family in Napa Valley.

The growth of the California wine industry during this period was substantial. To give you an idea, the areas planted with vines exploded from about 3,000 acres to more than 20,000 planted acres over the past decade in just Napa Valley!

The start of the 20th century in the California Wine Business: This was a time of growth for California wine. 1904 saw the creation of Beaulieu Vineyards by Georges de Latour. Prior to the purchase by Latour, the property was known as the Ewer and Atkinson Winery.

Before the start of the next century, more than 200,000 acres of vines were planted in the state. This was too much for America to consume. Overproduction and the lack of demand due to the depression were to blame.

Another factor that led to problems with the burgeoning California wine industry was that much of the massive quantity being produced was done without thought to quality or grape varietals. This led to the creation of the California Wine Association in 1894.

The California Wine Association as a trade group endeavored to raise prices and demand. Other wine trade groups quickly formed and tried competing, which in turn led to what became known as the wine wars of the 1890s. The eventual result proved to help the Napa Valley become America’s greatest wine-producing region.

This took place because, for the first time, quality standards were enacted. Producers were able to charge more money for the quality of their wine. Labels began stating if the vineyard was planted on a hillside or the valley floor. More importantly, the Mission grape was rapidly being replaced with better European grape varieties. Wine quality was improving and this helped foster demand.

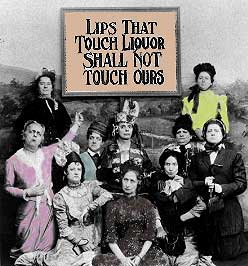

The Volstead Act, Prohibition: Everything was starting to come together for the California wine industry until the ridiculous Volstead act was passed in 1919.

The Volstead Act, better known as Prohibition, which outlawed the sale and production of alcoholic beverages, decimated the California wine industry. It also hurt state and federal tax revenues, as taxes on alcohol were high. To make up for lost revenue, sales taxes started being collected by the states.

With special permits from the Prohibition Department, some producers were allowed to make wine and brandy during Prohibition. Some of the larger companies at the time were the French-American Wine Company, The California Wine Association, Italian Swiss Colony Wines, and the Louis Martini Product Company which eventually became the Louis Martini Winery.

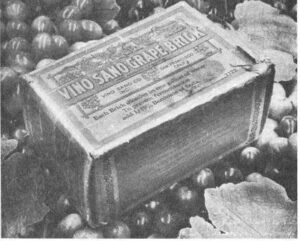

To survive, the larger companies sold grape juice in barrels with heavy amounts of S 02, also known as Sulfur dioxide. When the barrels were opened, and enough air was added to the grape juice, the fermentation process could begin, which turned the grape juice into wine.

Most people just gave up, abandoned their land, and allowed their vines to die. The few that stubbornly remained were reduced to selling Sacramental wines at best, or dry must, better known as raisin cakes to home winemakers that produced their own wine for so-called religious purposes.

The raisin cakes were sold with explicit instructions on how not to allow the product to develop any degree of alcohol, which of course was a not-so-secret code that informed consumers how to make wine.

There was also demand for industrial wine, which as an example was sold to tobacco companies for use in macerating tobacco. The only other minor saving grace was the law allowed home winemakers to produce 200 gallons of non-alcoholic cider per year.

Even though grape prices promptly escalated, this was not enough to keep the wine industry afloat. Prohibition remained the law of the land until the 18th Amendment to the Constitution was repealed in 1932. While many landowners allowed their vineyards to die, other California winery owners, clever enough to get around the system, thrived and prospered.

To give you an idea about the devastation to the California wine industry during Prohibition, prior to 1919, more than 2,500 wineries were licensed to make wine in America. By 1933, less than 100 remained! At the time, much of the wine being produced was sweet-styled white wines, Sherry, and Port, although non-varietal red wines were also being made.

A few growers survived by selling their fruit as table grapes. By the time Prohibition was over, Alicante Bouschet, Petite Sirah, Zinfandel, Grenache, Cinsault, and Carignane were the most popular red grapes planted. Riesling and Muscat of Alexandria were probably the most prevalent white wine grapes in the vineyards.

Due to the near-death of the California wine industry, the vineyards were allowed to wither and die, as many had not been tended for years.

Interestingly, even though Prohibition was in full force during the decade of the “Roaring Twenties,” research continued on grapes, winemaking, and wine production thanks to the early efforts of Dr. Eugene Hilgard. In fact, the genesis of the future California AVA mapping began in the 1920s, when researchers determined that there were five, unique, climatic zones that wine growers should pay attention to in California.

Prior to this study, vineyard land was thought to come from only inland or coastal areas. The report also created a road map for the next generation of growers as to which grapes were best suited for California and equally as important, they advised removing numerous grape varieties that were planted in various portions in the field blends that had taken hold. The reason being, those grapes did not produce wine with commercial viability.

If Prohibition was not bad enough, the great depression of 1929 added even more problems to the California wine industry. Things did not begin to improve until the late 1930s. The rebirth was again stopped in its tracks when World War 2 broke out. However, the new generation of wine producers did not give up hope and began rebuilding the industry during the war.

The road for the subsequent generation of California winemakers was more than difficult. By the 1940s, Napa Valley was on its way to becoming fairly active again. Close to 6,000 acres were planted. At the time, some of the most popular wineries were Beaulieu, Beringer, Inglenook, Wente, Concannons, and Louis Martini.

Louis Martini became one of the first California wineries to bottle wines made from specific grape varieties. Inglenook was already selling wines made from Cabernet Sauvignon by 1934! Cella was the leading, inexpensive bulk wine producer. 1944 saw the formation of the Napa Valley Vintners Association thanks to the efforts of Louis Martini, John Daniel, Georges de Latour, and Martin Stelling.

In 1943 Martin Stelling began accumulating large parcels of land, including the To-Kalon Vineyard, which he purchased from the Churchill family, making Stelling only the third owner of the vineyard in 80 years. Martin Stelling eventually owned close to 2,000 acres of vines in the valley.

Martin Stelling along with Andre Tchelistcheff and Caesar Mondavi were among the first growers to recognize that Cabernet Sauvignon and the Napa Valley were a perfect match, made in heaven. Martin Stelling also introduced Sauvignon Blanc to the region in 1945. Sadly, Martin Stelling died in a car accident in 1950 at the age of only 47.

By the time Martin Stelling died in 1950, between 15-20 wineries were active in the Napa Valley and Sonoma.

The next generation of the most important people in the history of California Wine: If I had to pick a few of the most important people that brought life into the wine business in those formative years, my shortlist starts with Andre Tchelistcheff.

Andre Tchelistcheff was hired by Georges de Latour. Tchelistcheff moved to California from France and joined Beaulieu Vineyards in 1938. This was imperative to the history of Napa Valley and its further development. Andre Tchelistcheff was responsible for introducing many of the modern winemaking techniques that were used in Europe.

It was Andre Tchelistcheff who began thinking about frost protection during the growing season. Andre Tchelistcheff pioneered the need for proper sanitation and the use of small, French oak barrels for the aging of the wine.

Tchelistcheff also insisted that malolactic fermentation become part of the wine-making process. Andre Tchelistcheff eliminated pasteurization and introduced the technique of cold fermentation to increase the color and concentration of the wine.

Andre Tchelistcheff introduced modern, viticulture practices of Europe. He began replanting the vineyards with higher levels of density, reducing the amount of sulfur used in the vineyards, and more importantly, Andre Tchelistcheff focused on planting high-quality French grape varietals.

Robert Mondavi belongs on the shortlist of the most important people in the development of the modern California wine industry. Robert Mondavi left his family business, which owned the Charles Krug winery to form his own winery in 1965.

Robert Mondavi founded his winery in Oakville with 2 partners, Ivan Schoch and Fred Holmes. Their initial purchase consisted of 12 acres of vineyards that were owned by the Stelling family. Those acres are now used for the winery, cellars, and offices at the Mondavi estate.

Believe it or not, this was the first new winery built in the Napa Valley since Louis Martini constructed his estate back in 1933! It was a massive undertaking for Robert Mondavi at the time. His efforts and pioneering ideas on the production, as well as the sales, distribution, and promotion of the California wine industry changed everything.

Prior to Robert Mondavi, few wines were sold as a specific grape varietal. Although Cabernet Sauvignon was sold under that name by his family’s winery, Charles Krug since the 1940s, the concept of focusing on a few, specific grapes was the brainchild of Robert Mondavi.

In 1968, Ivan Schoch and Fred Holmes sold their shares in the fledgling Robert Mondavi winery to the Rainier Brewing Company. Robert Mondavi quickly took his profits and acquired 230 more acres of the To-Kalon vineyard. The following decade, the historic partnership between Robert Mondavi and Baron Philippe Rothschild of Chateau Mouton Rothschild that created Opus One in 1979 also broke new ground.

This allowed for greater access to the world market for California wines. Much of the grapes used for Opus One were planted in the original To-Kalon vineyard.

It’s interesting to note that even though Robert Mondavi was well aware that fruit from the To-Kalon vineyard was the heart and soul of their Cabernet Sauvignon, it took until 1987 to register the name and almost another decade before he began using the To-Kalon name on their labels promoting the vineyard as the grape source.

Cabernet Sauvignon comes to Napa Valley: The Mondavi family are responsible for countless developments in the California wine industry. Caesar Mondavi brought the family in 1923 to the Lodi area, which is where they began to become active in the wine business. They made their first purchase in Napa in 1934, when they bought the Sunny St. Helena Winery, which has since changed names to Merryvale.

That was followed in 1943 when they bought the 150-acre Charles Krug winery in St. Helena for $75,000. During the 1940s, the Mondavi’s were one of the first growers to remove their field blends and plant Cabernet Sauvignon, as well as other popular, French grape varieties.

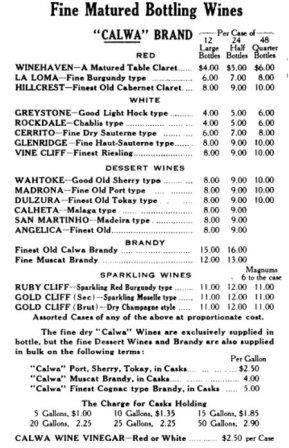

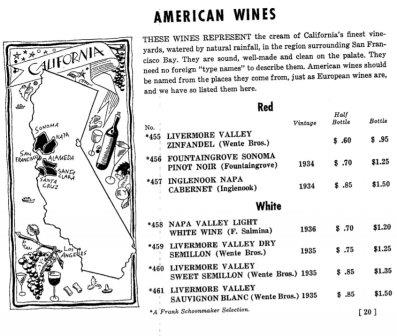

This is an important development. As you can see from this menu printed in the 1940s, California wines were just starting to be sold as specific grape varieties.

In large part, the success of Cabernet Sauvignon in the Napa Valley was due to the tremendous wines they were making at Charles Krug. It took until the 1960s and beyond before countless other growers began planting Bordeaux varieties in Napa Valley. In 1958, the Mondavi family bought 325 additional acres of the To Kalon vineyard for their Charles Krug winery.

In 1962, following Robert Mondavi’s first trip visiting the best wineries in Europe, Charles Krug began emulating the production techniques that were already in use in Bordeaux and other regions. Soon, other California vintners took the lead of Robert Mondavi and began aging their wine in small, French oak barrels.

Following in the footsteps of the Mondavi family at Charles Krug, Joseph Heitz founded Heitz Vineyards creating his winery in 1959. By 1966, Robert Mondavi released his debut vintage of Cabernet Sauvignon. He was soon followed by several other quality-conscious producers in subsequent years like Caymus, Chappellet, Diamond Creek, Joseph Phelps, Shafer, and Stags Leap, who all planted and produced Cabernet Sauvignon wines.

Sonoma County comes of age: The history of Sonoma shows that it developed along the same path as Napa Valley until Prohibition. But after that, the region fell behind. In 1957, Sonoma County was planted with field blends made of a myriad of different grapes.

Much of the credit for planting the correct grape varieties go to James Zellerbach. James Zellerbach founded Hanzell vineyards and began planting Pinot Noir.

Joseph Swan and Joe Rochioli followed in the footsteps of Zellerbach. Joseph Swan was the first Pinot Noir producer in Sonoma to truly popularize making wine using Burgundian methods, including whole-cluster fermentation, manual punch-downs, and aging in French oak barrels. The Pinot Noir clone created by Joseph Swan remains popular today.

Joe Rochioli was one of the initial producers of Pinot Noir to insist on making a wide range of single-vineyard designated wines. Following in the footsteps of Napa Valley, Sonoma was granted AVA status. Today, there are 18 unique AVA’s recognized in Sonoma.

The Judgement of Paris brings the modern age to California Wine: Clearly, California wine was gaining popularity in its home country. But its reputation paled to that of the more famous French wines.

That all changed when the now famous, “Judgment of Paris,” blind tasting took place, May 24, 1976. The idea was to pair the best wines of California against the best wines of France in a blind tasting. The thought was, French wines were so good, the event would promote the wines of France and trounce the California wines.

A panel was quickly convened, made of exclusively, French wine-tasting experts. The wines featured four White Burgundies against six California Chardonnay wines. The results shocked everyone because 3 of the top 4 wines were from California! Chateau Montelena, Spring Mountain Vineyard, and Chalone Vineyard were instantly famous.

For the white wines, the vintages were more tightly clustered than the red wines. 1973 Montelena, 1973 Chalone, 1973 Spring Mountain, 1972 Freemark Abbey, 1972 Veedercrest and 1973 David Bruce were pitted against, 1973 Mersault Charmes Roulot, 1973 Beaune Clos des Mouches Josephe Drouhin, 1973 Batard Montrachet Ramonent Prudhon and 1972 Pulingy Montrachet Les Pucelles Domaine Leflaive.

When the results for the white wines were announced, everyone was surprised. 1973 Chateau Montelena took the gold medal. Silver went to 1973 Mersault Charmes Roulot and the bronze award was handed over to 1973 Chalone!

Next came the red wines. 1973 Stags Leap Wine Cellars, 1971 Ridge Montebello, 1970 Heitz Martha’s Vineyard, 1972 Clos du Val, 1969 Freemark Abbey, and 1971 Mayacamas for California were led to the supposed slaughter. Like gladiators, 1970 Mouton Rothschild, 1970 Montrose, 1970 Haut Brion, and 1971 Leoville Las Cases were ready for battle.

French and American wineries were vying for the championship and the spoils of war, meaning massive increases in sales would quickly be awarded to the victor. Two First Growths coupled with 2 Second Growths from the 1855 Classification were confident they had nothing to fear.

The California wineries were praying that even with such great wines facing them, and all assuredly biased French judges, their luggage was going to be heavier, due to the added weight of the winner’s medals.

Using a 20 Pt scale, the eleven judges turned in their scores and the results surprised everyone. Especially the Americans! The top spot in the tasting, which earned a gold medal was awarded to 1973 Stags Leap Wine Cellars! The silver medal went to 1970 Chateau Montrose, followed by 1970 Chateau Mouton Rothschild, which grabbed the bronze medal!

In those days, the news did not travel as fast as it does today. But everyone in the wine trade as well wine lovers all over the world was quickly made aware that the previously little-known American wines trounced the famous 1855 Classified Growths of Bordeaux in both the red wine tastings and that the California Chardonnay wines defeated the famous producers of White Burgundy.

The French Press barely covered the event. Perhaps due to the major embarrassment suffered by the French producers. In America, Time Magazine published the results. Once the dust had settled over the corks, instant recognition and increased sales and prices for California wines were the prizes. The modern era for the California wine industry was officially in full bloom.

Single Vineyard Wines are born. By the start of the 1970s, growers, winemakers, and some consumers were aware of the best vineyards. But very few wines were being sold as vineyard-specific bottlings. Ridge, Joseph Heitz, Al Brounstein of Diamond Creek, and Milton Eisele were the original early pioneers of making distinctive, single vineyard-designated wines in Napa Valley.

While the Eisele vineyard was given its now-famous name in 1969, the site dates all the way back to 1882. In those days it was planted to Zinfandel and Riesling. Credit goes to Heitz Cellars for producing Heitz Martha’s, which was released in 1966. Milt Eisele was next. But Eisele was a little different.

In 1971, Milt Eisele began insisting wineries purchasing his fruit include the Eisele name on their label, letting consumers know the grapes came from his vineyard. That trend has continued gaining popularity even today. While younger consumers take it for granted, in those days, it was revolutionary!

Because until then, consumers purchased wines based on the name of the owner, not the vineyard. In Sonoma County, thanks to the early efforts of Joe Rochioli of Rochioli Vineyards and Steve Kistler of Kistler Vineyards, that region also began producing single vineyard-designated Chardonnay and Pinot Noir wines. Wineries in the Central Coast are also bottling more single-vineyard-designated wines all the time.

Enter Robert Parker: Clearly, there were some estates making great California wine in the 1940s, 1950s, 1960’s and 1970s. But the truth is, those producers were far and few between. In fact, until 1967, the production of sweet wine was more popular than dry red wine in the Napa Valley.

By the time Prohibition was over, Alicante Bouschet, Petite Sirah, Zinfandel, and Carignane were the most popular red grapes planted. Riesling and Muscat of Alexandria were probably the most prevalent white wine grapes in the vineyards.

Very little Cabernet Sauvignon was planted in Napa Valley in those early days. Many California wines from that era were not made from ripe fruit. Several wines were overly acidic and did not age well.

Grape varietals were often planted in the wrong soils. Wines were still aged in redwood instead of oak in those formative years. Please note that I said many of the wines from Napa Valley and California in the 1960s and 1970s had problems. There were a handful of producers making great wine at the time as well.

It was an interesting time to become a wine critic. Robert Parker needed the Napa Valley and little did they know, but the Napa Valley wineries needed Robert Parker as well, as both were about to explode. Robert Parker started his career as a wine writer in 1978 when he founded what became The Wine Advocate.

Robert Parker, who became famous after his bold calls about the 1982 Bordeaux vintage loved California wine. He felt that many producers with great terroir were not making wine at their full level of potential.

His call for harvesting phenolically ripe fruit, lower yields, more sorting and selection, cleaner facilities, and using more new, French oak barrels, coupled with planting the right grape varietal in the correct soils along with producing more vineyard specific wines was heard by many winemakers.

By the late 1980s, things started heating up in California. 1984, 1985, 1986, and 1987 ushered in the first wave of the new era. It became clear that making better wine, earned you better scores from Robert Parker. Higher scores quickly translated into more money and things began to change. This became more apparent during the 1990s, which was seen by many as the first, golden decade for California wine.

The explosion of high-end, producers took hold once the 1990s came around. Several of the most famous estates today began producing wine during the incredible decade of the 1990s. 1990, 1991, 1992, 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996, and 1997 brought about an unequaled run of great vintages and improved levels of quality to California wine.

The popularity and power of Robert Parker was also on the rise. His enthusiastic praise made overnight success stories for the best producers. This was coupled with equally higher prices, which many people unfairly blamed Robert Parker for.

Introduction of AVA, American Viticultural Areas: In 1983, in recognition of the uniqueness of the terroirs and soils in the myriad of different vineyard sites, a system of AVA’s, American Viticultural Areas were created. The California AVA system certainly has its own quirks.

The oddest example of this is that wines are allowed to come from multiple AVA’s as long as the grapes are from only those AVA’s listed on the label and that the percentage of each AVA is listed on the label. The first AVA was granted to Napa Valley. The AVA system has continued expanding over the years. Today, the Napa Valley alone consists of 16 unique American Viticultural Areas, also known as AVA’s.

Los Carneros 1983

Howell Mountain 1983

Wild Horse Valley 1988

Stags Leap District 1989

Mt. Veeder 1990

Atlas Peak 1992

Spring Mountain 1993

Oakville 1993

Rutherford 1993

St. Helena 1995

Chiles Valley 1999

Yountville 1999

Diamond Mountain 2001

Oak Knoll 2004

Calistoga 2009

Coombsville 2011

As of 2021, there were 139 recognized different American Viticultural Areas in California. Petaluma Gap, in Sonoma, is the most recent area awarded AVA status. This is not without controversy.

There are many knowledgeable people in the wine industry that feel there are far too many AVA’s, as each area does not produce truly distinctive wine from that of its neighbors. On the other side of the coin, there are numerous growers complaining their soils and terroir are unique and deserve their own AVA. As the old saying goes, you can’t please all the people all of the time.

Birth of the true modern era for California Wines: Starting in 1990 and continuing almost unabated in the following decade, vintage after vintage proved to be stunning. This incredibly lucky streak of vintages allowed growers to produce better wine. While some winemakers refused to jump on the ripe fruit, soft tannins bandwagon, that is what consumers wanted to buy, drink and cellar. New wineries sprung up overnight!

To give you an idea of the recent, rapid growth of the California wine industry, it’s important to learn how quick and recent this growth really is in the modern era. In 1945, very few growers existed, and of course, even fewer wineries were making wine. 1955 saw 360 growers. 1965 – 232 wineries were active in California. 1975 saw 330 producers. 1985 – 712 producers were making wine. 1995 – 944 estates were producing wine. In 2005, 2,275 producers were making wine and today there is close to 4,000 wineries in California!

California Cult Wines: Some of the smaller estates, making extraordinary wine in small quantities became known as Cult wines. Most of these wines were made in such small numbers, they were often sold exclusively to their own, thirsty customers via a mailing list.

The first California Cult wine to be sold via mailing lists was Grace Family in 1978. This was followed by Williams Selyem, who produced Pinot Noir. Neither producer is considered a cult wine today.

The California Cult wine phenomena began taking hold in 1992. Abreu, Araujo, Bryant Family, Colgin, Dalle Valle, Harlan, and Screaming Eagle were all about to become legendary wines among wealthy collectors.

At first, the top cult wines were offered at reasonable prices. Most were available for $40 to $60 per bottle. Screaming Eagle was shockingly expensive at $75 per bottle! But the demand to taste the latest and greatest created a secondary market for any small production wine with a high, Robert Parker score.

Producers watched their customers reselling their wine the same day they purchased it for double or triple price wanted a piece of that action. Within a decade, prices rose on most wines so much, that the secondary market was effectively killed for all but a few wines. The price escalation wars eventually stopped. But there is no price reductions insight.

Today, very few wines sell for more money on the secondary market. There is one wine that remains on the top of the cult wine pyramid, Screaming Eagle.

Screaming Eagle continues setting the standard all other high-end, or so-called Cult wine producers emulate. Their first release in 1992 was offered to a small list of insiders for about $75. The wine quickly jumped to $500 per bottle. Today, it sells for more than $5,000 per bottle! Screaming Eagle remains the last true, cult wine.

In 2014, the price from the winery was $750 per bottle. The Secondary market quickly pushes it to $1,500 per bottle and beyond. Today, Screaming Eagle Cabernet Sauvignon sells for more than $1,000 per bottle direct from the producer. However, the most expensive wine from California is a white wine. Screaming Eagle Sauvignon Blanc sells for more than $5,000 a bottle in the secondary market!

By 2007, some consumers and a few wineries created a minor backlash against the wines championed by Robert Parker. Claiming the wines would not age and were too big to be enjoyed with meals. Clearly, they were wrong when it comes to age as many of the first waves of California wines made with phenolically, ripe fruit, with their increased sugar and alcohol levels have aged for decades.

With consumers continuing to buy these wines in droves, Robert Parker will always be remembered as being one of the most influential people in modern the age of Napa Valley. But Parker is not the only person on the podium.

The most influential people in California wine today begin with Bill Harlan. The contribution of Bill Harlan in creating the modern era of Napa Valley cannot understand. His dream of creating an estate in Napa that rivaled the First Growth wines of Bordeaux certainly came true.

The way that Bill Harlan developed his brand as a luxury item, selling to an exclusive marketing list, in advance of Robert Parker’s scores remains unrivaled.

The creation of the world’s first wine, a country club for the jet set, with the Napa Valley Reserve remains a first. Bill Harlan is a perfectionist. He created Harlan Estate in 1984 and did not release any wine until 1991, because he demanded perfection.

Bill Harlan did the same with his next venture Bond and his newest project, Promontory, which made its debut in 2014. Bill Harlan is also the developer of Meadowood Resorts in Napa Valley.

David Abreu is the most successful and influential vineyard manager of all time. And this takes into consideration probably every viticultural area in the world. Think about this. Harlan, Araujo, Colgin, Screaming Eagle, Dalla Valle, Bryant, Spottswoode, Staglin, and Pahlmeyer are just a few of the famous names he works with on their vineyards.

After several visits to the best vineyards in Bordeaux, David Abreu began applying much of what he learned to vineyards in Napa Valley. David Abreu was a major proponent in planting vineyards with better clonal selections, the right rootstocks, tighter spacing, and getting the correct varietals placed in the best microclimates. He single-handedly popularized vertical trellising and hedging in the Napa Valley.

David Abreu also produces one of the best Cabernet Sauvignon wines in the Napa Valley with his eponymous Abreu Vineyards wine. David Abreu is the third generation of his family to take hold in St. Helena. He founded Abreu Vineyards with purchase in 1986 of the Madrona vineyards. The success of David Abreu is not without controversy.

It is said that in his quest to create new vineyards, land not designated as vineyards, trees, rocks and other natural formations were destroyed.

The most notable example of this was in the creation of Bryant Family Vineyards on Pritchard Hill which required cutting down hundreds of oak trees in violation of land-use rules and laws. The Napa Valley Zoning Commission levied fines and at the end of the day, the new vineyards were thriving in the Napa Valley and producing great wine.

Andy Beckstoffer is the most powerful grower in Napa Valley with more than 1,000 acres of vines in the Napa Valley.

Andy Beckstoffer also owns thousands of acres of vines in Mendocino and Lake Counties. Andy Beckstoffer is unique because, unlike other growers, he does not make wine. He sells grapes and licenses the name of his vineyards, primarily Beckstoffer Vineyards and To-Kalon, to a myriad of the producers in the Napa Valley.

Andy Beckstoffer got his start in the wine business with the Heublein company in 1966. In 1972, he purchased 1,000 acres of vines with his new company, NAPACO, the Napa Company which he owned a majority share in, along with the Heublein company.

Part of that purchase included 89 acres of vines planted in the To-Kalon vineyard. At the time of the purchase, the To-Kalon vineyard was in dire need of replanting.

There were also problems due to phylloxera, along with Merlot and Petit Verdot that needed to be ripped out and replaced with Cabernet Sauvignon. When the vineyard was replanted, Andy Beckstoffer was one of the first growers to recognize planting vines with tighter spacing, similar to what had been taking place in the Left bank of Bordeaux for ages.

Some of the best parcels owned by Andy Beckstoffer today include the 89-acre parcel in the To-Kalon vineyard. The To-Kalon vineyard is one of the top sites in the entire Napa Valley, As we said earlier, the vineyard was originally planted in the 1860s by Henry Crabb.

To-Kalon took its name from Greek, when translated, it loosely meant, the highest beauty, or the highest good.

Andy Beckstoffer bought his share of the To-Kalon vineyard from Beaulieu Vineyards in 1993. The only other wineries that own part of the To-Kalon vineyard, with the rights to use the fabled name today are Robert Mondavi, and other wineries owned by Constellation Brands, which purchased Robert Mondavi.

The To-Kalon parcels owned by the Detert Family and the MacDonald family, which include some of the oldest Cabernet Franc vines in Napa, planted in 1949 and Cabernet Sauvignon, planted in 1954 do not come with any rights to use the To-Kalon name.

While most agricultural products are sold by weight, what makes the Beckstoffer system unique is how he prices his grapes. Prior to 2015, Andy Beckstoffer had been charging a set price for To-Kalon grapes based on a set price per acre, per ton, and an arrangement that allowed him to participate in the profits on the wine, a set multiplier based on the price of the wine.

Generally speaking, the price is tied to the price of the bottle of wine. For example, a producer selling his wine at $300 per bottle will be paying $30,000 per ton of grapes making the cost equal to 100 times the price of the bottle!

With that, producers are also allowed to list the name of the vineyard on the bottle, for example, Beckstoffer, Dr. Crane, or the recently purchased Hayne Vineyard. That was the relative formula for years.

It was expensive, but numerous wineries, many of which were receiving the highest scores by Robert Parker and massive critical acclaim from consumers were produced from grapes planted in the To-Kalon vineyard. But in 2015, Andy Beckstoffer announced a game-changing price structure when he told growers there would be a massive increase in price when their current contracts expired.

The new pricing structure would be based on the familiar formula of a set price per ton, an agreed-on price per acre and to ensure the maximum amount of participation for Beckstoffer, the set multiplier for the wineries agreed on retail price.

What made things different is that starting in 2015, the new multiplier was set at a whopping $18,000 per ton of grapes or 175 times the bottle price per ton. The winery would pay the higher price of course

The kicker was that wineries would also pay no less than $45,000 per acre, to avoid price decreases to Andy Beckstoffer in case of the low yields! Using simple math, wines selling for $300 or more, (which is not out of the question for high-scoring Napa wines) were paying no less than $50,000 for each ton of grapes they purchased!

However, all was not golden with Beckstoffer To-Kalon grapes. Some winemakers complained about high yields, and with such a large vineyard, not all parcels had the same level of terroir, so of course, the quality of the grapes varied.

The minimum price for any wine bearing the Beckstoffer To-Kalon name on the label was set at $125. The net effect of the price increase is not yet known, but the best wines are going to cost consumers more money, and smaller wineries that had been making wine from To-Kalon fruit will be unlikely to continue.

Wineries with a business model that allowed them to sell direct to consumers were fine. But wineries selling through middlemen or wholesalers were going to have a very hard time making any money with this new arrangement.

Beckstoffer showed other growers this new way of pricing grapes, as they were the ones taking the risks, and this drove up prices from every other source in the region.

The valuable name of To-Kalon has caused contentious lawsuits between Andy Beckstoffer and the Robert Mondavi winery, regarding the legal rights of placing the name on wine labels. The first suit was filed in 2002 By Robert Mondavi against Schrader, who filed a countersuit. This was followed by another suit by Andy Beckstoffer against Robert Mondavi.

The suit was settled with Andy Beckstoffer winning the rights to allow wineries the use the name To-Kalon on their wines. By 2016, perhaps 20 different wineries were able to buy grapes from To-Kalon. In theory, every winery must state the Beckstoffer To- Kalon vineyard designation on the wine label.

Helen Turley had a big impact on how wines are made in the Napa Valley and throughout California today. As a consultant, she worked with numerous wineries, starting with BR Cohn before moving on to La Jota, Colgin, Bryant Family, Pahlmeyer, Kapcsandy, and Turley.

Helen Turley broke all the established rules at the time, changing the way wines were made in California. Turley was perhaps the first winemaker in California to use cold soaks.

Helen Turley was one of the first winemakers to focus on harvesting phenolically ripe fruit. Her goal was to try making the wine as natural as possible. To do this, she did not acidify. This went against the grain at the time. She did not clarify wine before placing it into the barrel and avoided fining and filtering during the bottling process.

Her belief was that all those processes stripped a wine of its character. Helen Turley earned a reputation for being more than difficult to get along with. So today, all her efforts are focused on her own winery, Marcassin Vineyards, which makes what many people feel is the benchmark for Chardonnay produced in California.

Aside from being a strong force in helping create the California Cult wine phenomena, Helen Turley also paved the way for future generations of female winemakers in California.

The future of the Napa Valley in part, is going to be difficult for two main reasons. First, most of the Napa Valley is already planted today. The few potential vineyard sites left are situated on land that is too steep to be farmed or the zoning commission refuses to allow plantings in those areas. With little or no potential for growth, sooner or later, prices for land and wine will continue rising.

The next issue is the potential of a problem that will take place as the drought in California continues, which of course, could be exacerbated with continuing rising temperatures. Wines from the Napa Valley are often compared with Bordeaux, due to the similar grape varieties. It’s interesting to note that while the regions share virtues, they do not share the same problems. In Bordeaux, they suffer from too much water.

As we enter further into the 21st century, the opposite problem is taking place in Napa, as they are experiencing what could develop into drought conditions. In time, the value of water and prices for water looks like it’s going to become a major issue. Many vineyards in California require irrigation.

With the heat, sunshine, and climate change, it remains to be seen how many vineyards can be successfully dry farmed. The water tables are considered by many to be too low. Plus, vines in California do not as a rule live as long as those in France.

They have more trouble during their lifespan finding ample nutrition, as they lack the time to live long enough to burrow really deep into the soils. Another issue is that vineyards are competing with farms that produce food, which is also in desperate need of water.

This issue is going to make it more difficult for established vineyards to expand and irrigate when needed. Potential new laws for planting new vineyards could become onerous.

This situation will become worse if potential new laws are passed in regards to regulating the amount of water one grower is able to use over another. Dealing with too much water, or drought is common practice in Bordeaux as well as the law. Perforce they are quite experienced with dry farming in Bordeaux.

When you also take into consideration both regions have the same grapes planted in poor soils, it is a natural fit for growers in one region to become interesting in expanding their holdings across the water. Except for Jess Jackson who has a vineyard in St. Emilion, not many vintners from California have purchased land in Bordeaux.

Since 1979, when Baron Philippe Rothschild entered into a partnership with Robert Mondavi to found Opus One, several winemakers from Bordeaux have invested in California. In fact, the other branch of the famous Rothschild family that possesses Chateau Lafite Rothschild owns the majority of the Chalone Wine Group.

The owner of Chateau Latour purchased Araujo. LVMH owns Newton and Chandon, Christian Moueix owns Dominus, the Tesseron family of Pontet Canet bought in Napa Valley on Mt. Veeder with Pym-Rae, and so did the Chanel Group withSt. Supery.

While Northern California wineries earn most of the press, numerous outstanding wineries continue springing up in the Central Coast area. Even though vines have been planted in the Central Coast as far back as the 1700s, until recently, the region was not producing world-class wine.

Like much of the California wine industry, The Central Coast was decimated by Prohibition. Growers slowly returned to the region in the late 1960s and 1970s.

The Central Coast is a massive region that stretches almost 250 miles long and 25 miles wide. The Central Coast AVA runs from as far south as Ventura and Santa Barbara to just south of San Francisco. Close to 15% of all wine in California is produced in the Central Coast today.

Close to 360 different producers are making wine from almost 100,000 acres of vineyards. The naturally cooler terroir was perfect for Syrah, Chardonnay, and Pinot Noir. The warmer parts of the appellation, found in the east was better suited for Zinfandel.

The southern end of the Central Coast seems to be the region’s hotbed for growers today. The 27,600 acres in San Luis Obispo County and 16,600 acres planted in Santa Barbara County are the home for some of the best young producers in the Golden State.

The undisputed star of the Central Coast region is Manfred Krankl who producers world-class wine from Rhone grape varietals. The wines Manfred Krankl is making at Sine Qua Non from their Syrah and Grenache vines are truly benchmark wines for all of California.

Today, Sine Qua Non is in contention for the number one most sought-after wine in California! Alban is another force to be reckoned with in the Central Coast. In fact, there are dozens of hot, young producers who make great Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, and wines from Rhone Varietals in the central Coast. Jonata is making very strong wine in the Santa Barbara region today.

Paso Robles has been known for producing stellar wines since the 1980s. Actually, you can go a lot further back than that as the Ueberroth vineyard, which is used by Turley was planted in the 1880s! In 2008 Paso Robles was granted AVA status. In 2014 the region was further recognized for its diversity when they added 11 new AVA’s.

The Central Coast region is also suffering from a lack of water, although the close proximity to the Pacific Ocean is helping some growers more than others, with their easy access to the oceanic climate.

Other regions in Southern California are also producing wine. The Malibu area has recently been granted its own AVA. Los Angeles has a few local wineries located due east of the downtown area. With the exception of Moraga vineyards, which is located in the expensive area of Bel-Air, California, none of the Los Angeles-based wines are truly interesting.

Wines are also made in Temecula, which is northeast of Los Angeles and close to San Bernardino and Riverside. Those wines in style are on the light, simple side. However, Temecula has a long history of producing wine. Vines were first planted in Temecula in 1820. The first official winery in modern times opened in 1974. By 2017, 40 wineries were operating in the region.